|

Tired of reading? Listen to a recording of this article or download it for later.

|

By SALIM FURTH, EMILY HAMILTON AND BRIAN HODGES

Rebounding from the COVID-19 crisis requires great private investments alongside public efforts to restore economic vitality. Cities that attract and accelerate those private investments — in jobs, housing and human services — will be well on the way to a complete recovery.

Where housing costs are high, allowing new housing construction is low-hanging fruit as an economic recovery strategy. New housing investments boost tax bases and attract workers and entrepreneurs. Housing expansion also eases financial strains for existing residents by slowing rent growth.

Three steps can address long-standing challenges in most cities that are exacerbated by the COVID-19 crisis: safely housing the homeless, encouraging rapid re-use of vacant space and streamlining regulatory approvals.

Safely Housing the Homeless

Homelessness is not a new problem in cities, but it may become more widespread and riskier because of the COVID-19 crisis. Although homelessness is more closely linked to high housing costs than to poverty, it is likely to rise in 2020 as employment collapses. Providing safe places for the very poorest to live is not only a matter of improving public health, it’s directly related to the underlying purpose of economic policy: creating an environment where every resident can thrive.

Traditional dormitory-style shelters may also spread viruses, and homeless people may be understandably hesitant to risk sleeping in them. Since homeless people come in frequent contact with the healthcare system, their exposure to contagion creates additional risk for medical professionals and other patients.

Cities can ease the costs of homelessness, both in traditional and contagion terms, with single-occupancy shelters. These include sheds, tiny homes, 3D-printed homes, converted motels and even vehicles owned by homeless people. These can be publicly or privately funded and delivered.

Cities can ease the costs of homelessness, both in traditional and contagion terms, with single-occupancy shelters. These include sheds, tiny homes, 3D-printed homes, converted motels and even vehicles owned by homeless people. These can be publicly or privately funded and delivered.

In virtually all cases, using single-occupancy shelters requires either case-by-case or blanket exemption from zoning laws. For example, cities could give all non-profits permission to provide shelter for the homeless in their buildings or in temporary shelters on their land, such as a portion of their parking lots.

Cities and non-profits can also provide services to clusters of single-occupancy shelters. At the most basic level, assigning overnight police protection to a specified parking lot protects people living in their cars and RVs.

Individual bathrooms – as in a converted motel – are ideal for controlling contagion. But in most cases, shared bathrooms, or even portable toilets, are an improvement on the absence of dedicated bathrooms. Local governments should install, or allow non-profits to install, portable sinks as well so that people can properly wash their hands after using shared toilets.

Spotlight

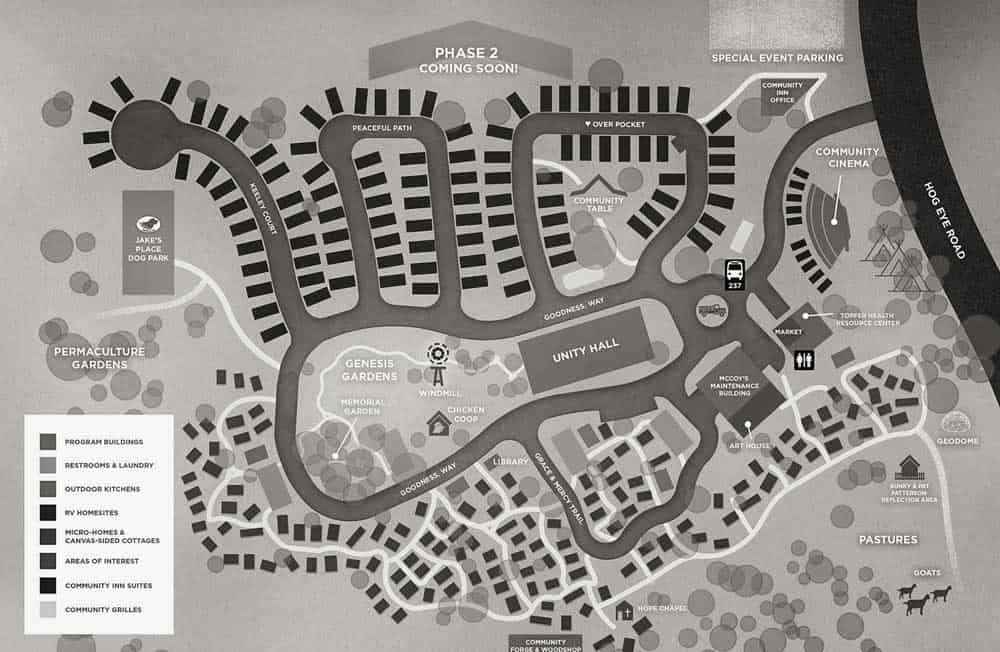

Community First! Village in Austin

Just beyond the city limits of Austin, Texas, Mobile Loaves & Fishes built a master-planned community for people who had experienced chronic homelessness. Their 51-acre site includes RV parking places, cottages and a central hall. Mobile Loaves & Fishes builds many services into the Community First! site, including several businesses where residents earn a living. It looks like a state park campground. But unlike a campground, the village needs to be located near the jobs, commerce and customers that the surrounding city provides.

The village’s FAQ explains its zoning: “Community First! Village sits just outside of the City of Austin city limits; therefore, there is no zoning. We do, however, have to comply with certain state regulations involving density and water quality.” In zoned areas, regulatory approval would be necessary to introduce the Community First! model. Cities can work with non-profit partners to identify and re-zone specific sites for village-style occupancy.

Repurpose Commercial Space

After a major dislocation, economies come back differently. We don’t know exactly how things will change, so cities will need flexibility to rapidly return to a thriving economy. Every sector of the economy is being hammered by the COVID-19 crisis, but commercial space – both retail and offices – can expect the most vacancies.

Many individual shops and retail chains will go out of business; in-person retail may permanently lose market share to online sales. Restaurants may do a larger share of business via delivery, reducing their demand for floor space.

Offices have had a crash course in remote work and workers have had a taste of working from home – it’s likely more workers will seek remote-work accommodations. As the recession continues, we expect some companies will ditch their office leases as the least disruptive way to cut costs. Other companies may move toward a campus model, with a mix of office time and remote work.

By contrast, residential demand should remain comparatively strong, especially in lower price tiers. Many cities came into 2020 with pent-up demand. The Great Recession showed that even a housing crash did not lower rent much in high-cost cities. And in most places, home prices rebounded within a few years.

Resilient residential demand and declining commercial demand can be accommodated by allowing re-use of vacant commercial space. This could be accomplished with a text amendment to local zoning codes to loosen use restrictions in commercially-zoned areas:

- Include single- and multifamily housing as an allowed (by right) use in zones that currently allow offices and substantial retail.

- Waive parking requirements, setbacks and bulk restrictions for re-use of existing structures. In Buffalo, the removal of parking minimums for re-use unlocked vacant downtown buildings that had not been viable under the previous zoning.

Commercial strips with a handful of residential conversions mixed in will be healthier than those with a handful of long-term vacancies. And commercial conversions may provide the type of moderate-price alternative housing that industrial loft conversions provided a generation ago.

Some cities will want to pursue these policies on a discretionary basis – granting variances and special permits rather than passing a text amendment. That approach would likely have limited benefit, since only well-capitalized builders will risk being stuck with distressed commercial property.

Streamline the Housing Construction Approval Process

Approval processes vary widely across localities. In some jurisdictions, projects generally proceed “by right” — projects that comply with zoning rules receive straightforward approvals and building permits. In other cases, cities require long, costly approval processes to secure permits, and what will (and will not) be approved is unclear at the outset. One statistical study found that the time that it takes for proposed housing developments to receive approvals is the most consequential aspect of regulation. The following section on accessory dwelling units offers a potential path to removing subjectivity and speeding up permit times for this relatively low-cost housing typology.

Some cities have elements of the approval process that empower residents who oppose new housing in their neighborhoods. For example, Washington, DC, has 40 elected Advisory Neighborhood Commissions (ANCs) that hold public meetings and issue advisory opinions on proposed developments. The city’s zoning and review boards make the final call, but they must give the ANC’s recommendations “great weight.”

Even jurisdictions without hyperlocal elected bodies often rely on public meetings where residents can express whether or not they like new development proposals as an important part of their housing approval processes. But research shows what many city officials likely already know; attendees at public meetings are not representative of their communities. Attending meetings requires residents to have the time and resources to spend voicing their opinions about changes in their neighborhood or city. Attendees unsurprisingly tend to be older and wealthier than the average resident in their jurisdiction, and they’re more likely to be homeowners. Further, discussing specific development proposals at public meetings tends to draw out opposition rather than gathering a representative sample of a neighborhood or localities’ opinions about new housing construction.

Each discretionary step in the permit approval process contributes to the “vetocracy” that stands in the way of new housing supply.

Each discretionary step in the permit approval process contributes to the “vetocracy” that stands in the way of new housing supply. Many bodies have the ability to delay or block new development, but people with the widely-held view that more housing should be available at lower prices don’t have an opportunity to override the vetoes of specific projects.

In housing development, time is money, and requiring developers to sit on projects — and loans — for months or years contributes substantially to construction costs. Delays in permitting directly increase the costs of home building and, in turn, eventual rental and sale prices for housing. And increases in the time it takes for new housing construction to be approved ultimately results in fewer viable housing developments. Further, when approval processes are uncertain, homebuilders will propose fewer housing projects than they would otherwise because seeking approval may cost thousands or even hundreds of thousands of dollars for an uncertain return.

For a model of streamlined permitting, local policymakers should look to Houston, arguably the most pro-housing city in the U.S.; since 1990 Houston’s population has increased by more than one-third, yet its median house price is lower than the national median. Houston does not require any discretionary review, and it even offers 24-hour permitting for single-family developments and simple commercial projects.

Houston’s process also offers public health benefits; unlike other cities, the Houston online approval process doesn’t require meetings, or even a trip to the planning department. Decreasing contact will make city employees and residents safer.

Spotlight

Ending Citizen Advisory Councils in Raleigh

In 2020, the Raleigh, North Carolina, city council voted to eliminate the city’s Citizen Advisory Councils. One of the councils’ roles was to make recommendations about whether or not to approve development proposals to Raleigh’s zoning commission and city council.

Newly-elected pro-housing city council members pointed out that the councils favored participation from the slice of Raleigh residents who have the time and resources to participate in long meetings. Requiring projects to go before the councils also slowed down approvals, raising the cost of housing construction and in turn reducing new housing supply.

Raleigh officials have said that they are seeking new platforms for citizen engagement that better reflect the interests of all residents.

Housing Production: Setting Accessory Dwelling Units Free

Addressing the housing shortage endemic in most cities is a key part of economic recovery.

The COVID-19 pandemic highlights housing as a basic human need that, when met, has communitywide health and social benefits. And, as cities move forward with their recovery efforts, housing — its construction, affordability and suitability to the population’s needs — can be a big driver of economic growth and resilience.

But too few homes are being built and they are too expensive. It’s as simple as that.

Earlier this year, Freddie Mac estimated that the U.S. needs an additional 2.5 million homes to accommodate the households we already have. This figure, however, does not capture the full extent of the housing shortage because it does not include the projected need for new housing over the next decade. Nor does it take into account the skyrocketing home prices that have made purchasing or renting in metropolitan areas difficult, if not impossible, for many people — particularly in larger cities like Los Angeles where “affordable” housing can cost up to $1 million dollars for an apartment.

Building more homes requires more buildable land or more density on existing land — things most major cities limit via zoning. Existing rules may severely restrict new housing or repurposing via separate areas for single-family and multi-family homes or other mixed uses. Combined with large minimum-lot sizes or restrictions on who can live on a property, these policies prohibit the flexible density needed to address the housing shortage.

Increasing Housing Quickly With 3 Levers

Move To Legalize ADUs

This addresses a gap in most cities’ housing supplies.

End Occupancy Restrictions

Cities should reform rules that restrict who can share a home.

Reform Permit Reviews

Predictable processes lower costs and speed development.

STEP 1: Legalize ADUs

Allowing homeowners to construct ADUs — tiny homes, in-law apartments or granny flats — with relative ease on lots zoned for single-family use will substantially expand the supply of small, affordable homes. This is critical for middle- and low-income households that are increasingly strained to afford housing in urban areas where most jobs are located.

While an ADU will not replace the need for a family home, such units play an important role in making more use of less land. ADUs also provide social benefits to families and communities because they often result in multi-generational households that reduce the demand on apartments and/or assisted living. And when not used for family members, ADUs provide an opportunity to add new rental units that can assist homeowners with mortgage payments.

Cities can further improve affordability by streamlining ADU permit-approval processes. Adopting rules that, for example, pre-approve architectural designs or exempt ADUs from regulatory fees imposed on new single-family development can drastically reduce the cost of building ADUs, spurring an increase in supply.

Spotlight

Portland and San Diego

In 2020, the Raleigh, North Carolina, city council voted to eliminate the city’s Citizen Advisory Councils. One of the councils’ roles was to make recommendations about whether or not to approve development proposals to Raleigh’s zoning commission and city council.

Newly-elected pro-housing city council members pointed out that the councils favored participation from the slice of Raleigh residents who have the time and resources to participate in long meetings. Requiring projects to go before the councils also slowed down approvals, raising the cost of housing construction and in turn reducing new housing supply.

Raleigh officials have said that they are seeking new platforms for citizen engagement that better reflect the interests of all residents.

Step 2: Remove Occupancy Restrictions

For the ADU strategy to work, cities should also reform rules that restrict who can share a home. Many cities have occupancy restrictions in their zoning codes that insist that a home or apartment be occupied by family members, prohibiting the number of unrelated people that can share a house or live in an ADU. These rules stifle increasing housing capacity by restricting who can live in the newly built homes.

Spotlight

Santa Clara

In Santa Clara, California, the median price for a single-family home exceeds $1 million and the average rent is close to $3,000 per month.

Since enacting laws to streamline the ADU permit process and eliminating many regulatory costs, Santa Clara has reduced the average cost by as much as $60,000.

Currently, the average cost of an ADU ranges from $80,000 for an attached unit to $160,000 for a detached one — a small fraction of the cost to rent or buy a home.

Step 3: Limit Costs

Permit-review costs drive home prices. As the housing and zoning section shows, costs and impact fees imposed during the permitting process can significantly increase the cost of ADUs. Rolling back the regulatory mark-up on permitting significantly reduces the cost of each new unit.

Another way to limit cost is to recognize that simple projects like ADUs should not require an architect and extensive review. Cities can pre-approve a selection of common building plans and streamline permit review for projects using those plans.

Spotlight

Bellingham and Bowling Green

Bowling Green, Ohio’s zoning code contained a provision declaring it a misdemeanor for more than three unrelated persons from occupying a home together, regardless of the number of rooms or adequate parking. In 2019, a federal court declared the law unconstitutional, finding no reasonable basis for treating four unrelated individuals differently than four related people.

Bellingham, Washington, is home to a major university which attracts a large number of renters. The city code, however, contains an occupancy restriction similar to Bowling Green’s. In response to the Bowling Green case, the city decided to suspend enforcement of the law while the state considered a bill that would prohibit occupancy laws. That bill did not make it to a final vote and Bellingham’s occupancy law remains on the books.

The solution to this problem in Bellingham and elsewhere is in the hands of local government, which has authority to revoke its code provisions. Alternatively, the city could enact an ordinance prohibiting enforcement of occupancy restrictions as follows:

Finding that many unrelated occupant limits on households worsen the community’s housing shortage by preventing full utilization of homes, discriminating against nontraditional households and providing no public benefit, it is the intent of the city with this act to prohibit local governments from limiting the number of unrelated persons occupying a home.

Except for occupant limits on group living arrangements regulated by state or federal law, and any restrictions on occupant load of the structure as calculated by the applicable building code, the government may not regulate or limit the number of unrelated persons that may occupy a household or dwelling unit.

While broad solutions to the housing crisis require additional state and local reforms, the steps above allow cities to immediately expand the community’s housing capacity and sharply reduce the cost of new units. This, in turn, has positive downstream impacts on economic stability, resiliency and long-term growth.