|

Tired of reading? Listen to a recording of this article or download it for later.

|

By JOE COLETTI

You don’t need to be told that getting through the next couple years will be a challenge. Your first task was to deal with a global pandemic that spreads faster the more people connect. Like a business that books restructuring charges in a quarter when it’s losing money already, taking the opportunity now to set a strong financial foundation will help make future decisions easier and likely set up your city for greater successes.

The most effective response we knew in March was to close those businesses that most define our cities — the restaurants, bars, theaters, sports venues, hotels, churches, mosques, stores, gyms, salons, even libraries, schools and colleges — and encourage people to stay home. As the shutdowns went from two weeks to four weeks and beyond, businesses found it harder to stay alive and a public health threat also became an economic threat.

Now, it’s not clear when or how our economies will rebound. Some neighborhoods are hurting worse than others and some businesses will never recover.

While you struggle with the personal and social tolls on the place you love, and possibly even your own business, you also must balance the city’s budget.

But while you struggle with the personal and social tolls on the place you love, and possibly even your own business, you also must balance the city’s budget.

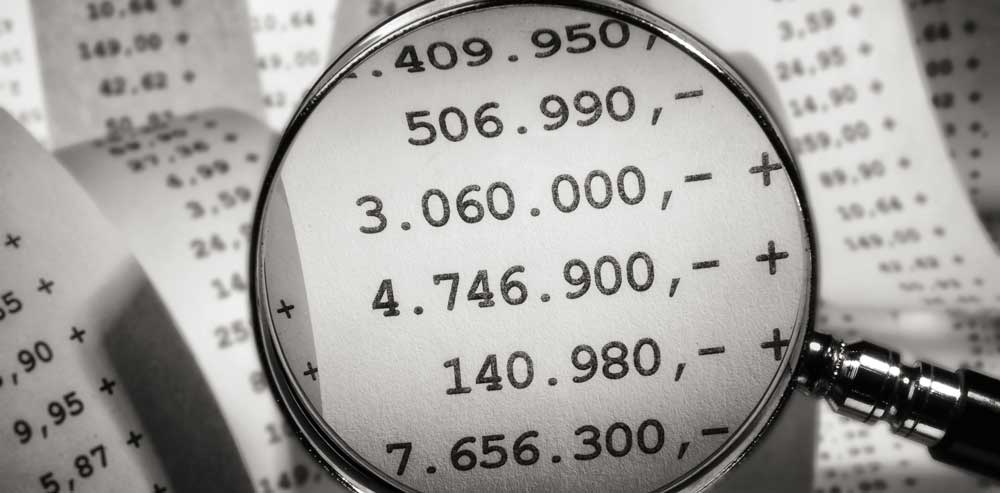

Sales taxes have fallen and will remain low for months, as will other revenue sources except maybe property taxes, which usually are paid through escrow accounts tied to mortgages. Many cities have provided grace for municipal water, gas and electricity, which means enterprise funds will also have less money.

Most municipal expenses, however, cannot shrink as much. Trash still needs to be collected. Police still need to patrol the streets. Buses still need to run, even with few riders.

What do you do?

Clarity can come from crisis, and this crisis may be an ideal time to reconsider the city budget from first principles on good financial management and good government.

Spending

You can’t out-earn bad spending habits forever. Cities and counties of all sizes have been raising taxes and dipping into reserves to cover day-to-day expenses – some as a matter of habit for years or even decades.

- Know what you have spent and what you will spend. This means tracking the bills that will be due in the coming months, when they are paid and how that compares to past spending.

- Control what you spend. Are there ways you can reduce the cost of programs you must maintain? What future obligations are you taking on with each dollar spent today?

- Use standard accounting principles. Comparing your spending with other local governments is a worthwhile and important yardstick – and you can bet that if you’re not doing the comparison, members of the media or citizens eventually will.

- Make it difficult to increase inflation-adjusted spending per resident. Circumstances will force you to run a lean budget this year. Residents and investors will be glad to see guardrails to keep spending growth in check even as the economy recovers and revenues grow. Restrained spending in the past would have helped now. Providing restraint now could make the crisis a little less painful.

Debt

Leverage is powerful, but with great power comes great responsibility.

- Limit total debt and limit how much locally generated tax revenue can be dedicated to principal and interest payments. Set those limits low and do not take on debt that would exceed them.

- Borrowing should not be used to increase current spending. In the recent past, it was tempting to take on debt to have more available for current expenses. Now, as then, the debt-service cost will be tacked on to other operating costs – exactly the wrong trendline for already-stressed city budgets right now.

- There’s no free lunch, even from the Fed. In the midst of the COVID-19 crisis, the Federal Reserve offered to purchase $500 billion in short-term debt from states, the 140 counties with populations above 500,000 and the 90 cities with populations above 250,000 to help them through the cash crunch.

This may look like a useful tool to help with cash flow, but most cities should be glad they don’t qualify and those that are large enough would do better to bear the pain now than to delay it and add even modest amounts of interest. Taking on debt to bridge lost revenue means when the debt comes due, today’s troubles will be competing with tomorrow’s immediate needs. The debt is not an investment that means higher revenue in the future, and given the deep uncertainty about the post-COVID economy, you want options not obligations. - If you do borrow, use debt for major capital expenses, not operations. Get voter approval to use general obligation bonds and make clear the property tax increase needed to pay for the new debt.

Revenues

There is always a temptation to increase taxes to paper over poor decision-making. Fiscal discipline comes not only from restricting revenue, but from restricting the number of revenue streams.

- Have a small number of taxes and fees so they do not mask the fiscal burden of government for you or your taxpayers.

- Make a tax on land or real property with limited exemptions the primary tool for raising local revenue. It provides more-consistent revenue and likely fluctuates less than a sales tax. Do your best to keep tax revenue neutral with each revaluation for the first year so tax increases are visible. It would be better to vote on revenue before spending.

- Use taxes to fund government and fees to fund specific functions. Do not use taxes or fees to coerce behavior modification.

- Limit the ability of general government or specific agencies to profit from fees and fines. For example, all receipts from fines and forfeitures go to education funding in North Carolina, which means municipalities have less financial incentive to write speeding tickets and people can trust their government more.

Spotlight

Back-to-Back Disasters Challenge Nashville

John Cooper knew when he became mayor of Nashville, Tennessee. that the budget was precarious. Spending had grown faster than revenue across city government, which left large and growing budget shortfalls — up to $41.5 million for the current fiscal year by the time Cooper was elected in November 2019. Then a killer tornado struck on March 2, taking the lives of as many as 28 people and causing an estimated $1.1 billion in damage. Less than three weeks later, the physical damage was matched by the public health crisis and economic devastation of the coronavirus.

Nashville is expected to lose $472 million over 16 months as a result of the pandemic. With no reserves to help, Cooper has recommended a 32% property tax hike to raise $332 million, savings and cost reductions of $165 million, and other revenue increases of $69 million. Some of the $122 million in federal assistance through the Coronavirus Aid, Relief and Economic Security (CARES) Act could help reduce the tax increase if Congress allows its use to offset lost revenue. His cuts have been minor, but 50% reductions in economic incentive payments and assistance to nonprofits and chambers of commerce could set the stage for more fundamental restructuring of city government. If reform does follow, Nashville’s fiscal crisis could leave the city better able to meet future fiscal threats.

State and Federal

Mandates and money go together like peas and carrots.

Look at your budget for what is necessary simply by being a city, what your residents want and what the city does to be eligible for state or federal grants. There are benefits and costs to creating a municipal government. Some costs are imposed by the state to ensure the city can carry out its core functions. Ensure residents know what those core functions are and managers understand their responsibility to keep costs low.

There are usually strings attached; consider them. Cities can improve their fiscal health by understanding and carefully weighing the liabilities created when voluntarily taking state or federal funds.

Have clarity about your assumptions and funding sources. Clearly indicate in budgets the amounts dependent on other government funding and the amounts mandated by state or federal governments.

Pensions

It is becoming trickier to balance the interests of retired workers, current and future employees, taxpayers and government beneficiaries. Few cities or states have enough set aside to cover the pension promises they have made to employees. Bad decisions made in the past affect those in office today and those who will be hired tomorrow.

In good shape? Lock in sustainability.

If your city is well-prepared for the future pension and health care needs of retirees, take steps now to ensure continued sustainability with lower discount rates, higher employer and employee contributions, and potentially changes in the plan for new employees.

On shaky ground? Focus on solutions.

If your city already cannot afford its promises to retirees, you will need to work with your citizens, employees and state government to balance employee benefits and current services. This is not easy at any time, but the need to tackle these difficult questions can be clearer in a crisis.

Bonding pension debt is a bad idea.

High general-debt levels only make this more complicated because bondholders are first in line to be paid unless a city declares bankruptcy.

Reporting and Oversight

The information needed to run government well is the same information residents, activists, journalists and businesses would want. Municipalities do not collect data on their operations and financials to make informed decisions on the best use of people or resources.

Make financial information understandable and available. This includes making Comprehensive Annual Financial Reports (CAFRs, pronounced “caffers”), available in a way that citizens can understand and compare to other local governments in your state. Post finances in a machine-readable format within six months of the fiscal year-end.

Meet or exceed Generally Accepted Accounting Principles (GAAP, pronounced “gap”) and Government Accounting Services Board (GASB, pronounced “gazz-bee”) statements in your reporting. Consider using accrual-based accounting for financial reports to know when costs are incurred, not simply when cash goes out.

Clearly account for liabilities such as pensions, retiree health benefits and infrastructure maintenance and replacement. Have that accounting independently verified.

With so many cities facing crises, states could respond with greater oversight. Be prepared for it. If your state does not already have one, it may create a commission to monitor local government finances, approve debt issuance and provide assistance in some cases. Such a commission could step in before a state would take over and appoint an emergency manager for a city.

Resiliency

As your finances recover, you can implement changes that will leave your city better prepared for the next crisis.

Borrow Less and Save More

Build savings to prepare for storms, other natural disasters and economic downturns. Once you have built an adequate reserve without taking on new debt for capital projects, you can make paying down existing debts and unfunded liabilities a priority.

Staffing, Equipment and Technologies Should Change With the Times

All three should be managed in a way that is responsive to changes in the economy or citizens’ needs.

Look For Ways to Save Money Through Shared Contracts

Natural partners include the state, ad hoc groups of cities with similar needs or intergovernmental associations.

Sharing Expertise Can Be a Source of Revenue

Some cities provide water to neighboring towns and others share fire departments and sheriffs’ deputies with their counties. IT and administrative services are also possibilities

No city will come through the current crisis completely unscathed, but some were — and more can be — better prepared. Applying these simple principles to your budget can help your city come out of this crisis stronger.